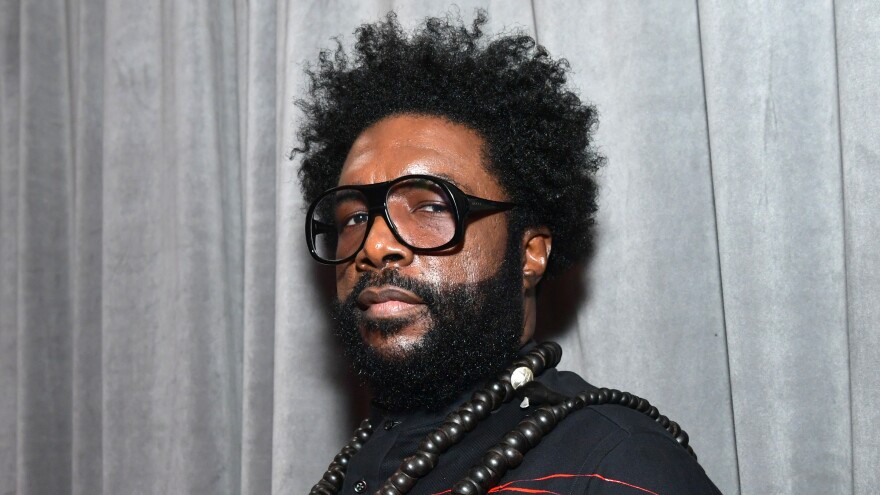

Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson is coming out of the pandemic a changed man. The co-founder of The Roots and the music director for The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon did something he never thought he'd do — he bought a farm in upstate New York.

"The last year has really been a big lesson for me in terms of self-love," Questlove says. "I was world famous for being a machine. ... I thought chaos was the only way that I could exist. But now I embrace quiet, and I can hear myself think."

Now Questlove has ventured into a new arena: He's made his directorial debut with the documentary Summer of Soul, which tells the story of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, a series of six free concerts held in what is now Harlem's Marcus Garvey Park.

The festival, which became known as the "Black Woodstock," featured performances from some of the biggest names in Black music, including Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Family Stone, Nina Simone and B.B. King. But footage of the concert wasn't broadcast widely, and memory of the festival had faded from history — until the documentary.

He says one of the best things about the film is the number of people who reached out to him to say they had unexpectedly seen a loved one among the 300,000 concertgoers. One person spotted their brother, who later died in Vietnam.

"They never had a photo of him. And somehow we had a close-up of him for like six seconds," Questlove says. "So that was really emotional for them to see him as a 19-year-old. So every day this is happening, people are getting their memories back."

Read the edited and condensed highlights from the interview below and listen to the full chat in the player above:

On how Tony Lawrence, the organizer of the festival, pulled off securing such an amazing lineup

Somehow he just managed and leveraged one promise on top of another based on what we call "FOMO," fear of missing out, like that. That was his friend. He's the original FOMO baiter. ... So it's sort of that was his level of, of negotiating but really just the audacity to dream.

Looking at the contracts, I was really shocked at what life was back in 1969. Like who knew that you could get Sly and the Family Stone for just $2,500? I wouldn't even pay that to my opening DJ. I realize that the inflation was there still, but yeah – Mahalia Jackson was the highest paid at $10,000.

On why the Black Panthers provided the initial security at the Harlem Cultural Festival

The Panther known as "Bullwhip," he was at the time, I believe, a young teenager. And he explained to us that at the very beginning, the police didn't want to provide security for the festival, basically because of what had happened the year before – of all the cities that sort of went into turmoil during the aftermath of Martin Luther King's assassination, Harlem probably got hit the hardest of all as far as rioting is concerned. ... So their response was basically, "We don't want to be anywhere near this, because we're going to be outnumbered," and that sort of thing. But I believe that as the weeks went on, by the second week, then [the police] realized, like, we'll provide security.

As a result, there was absolutely no incidents whatsoever, which, I hate to say this, but in comparing it to that other festival [Woodstock], if even 5% of the things that happened at Woodstock happened at the Harlem Cultural Festival, then there is a possibility that you would have heard of this festival.

On what surprised him most watching footage of the Harlem Cultural Festival

I would say probably the Sly and the Family Stone performance is probably the most shocking to watch at the time, because ... up until that point, Black entertainers were hyper-aware of their presence in the world, even if it was the professional sense. And so kind of rule No. 1 was always this sort of unspoken, "I come in peace, I'm not a threat," kind of disposition that most Black people have to have in the workspace, especially during this time period.

Motown was especially known for sending all their acts to charm school and whatnot, and their whole disposition was basically like, you must wear a tuxedo all the time. ... And so the fact that Sly and the Family Stone is performing in their street clothes is such a shock to the audience. ...

And then suddenly to watch them have more excitement than the kids at the end of a set, that to me is almost like that should be taught in every university, like on how to really engage and perform and really have a plan that's unmarked and unprecedented and really execute it to perfection.

On learning to embrace all kinds of music, which came out of social survival among white peers

As you can see with all my peers in hip-hop, a lot of us ... thought that not getting shot in the club was the victory. 'Ah, OK. I'm 35 now. I'm too old to get shot in the club,' because that was always a concern in the '90s. Now there's a new getting 'shot in the club,' which is strokes, cardiac arrest, our mental health and whatnot.

I knew early that my survival in whatever world that I create really depends on my education level, of what I knew, so that I could fit into that world. If you're in second grade and a bunch of your white musician friends are playing "Smoke on the Water," I have to investigate and study that.

A great example is [that], in order to watch "Billie Jean" on MTV, I had to sit through four hours of Def Leppard, of Phil Collins, of Thomas Dolby. ... Just sitting there just waiting for Michael Jackson to come on and suddenly all this other music is seeping into me. ... So I think in my case, it was a matter of social survival on how to relate to my friends at school. But then once hip-hop came along, then it's like, oh – everything I learned, I'm just going to add into this pot of stew I'm making. In a way it's genuine love, but in a lot of ways it's survival. ... I'm certain that if I didn't have this range of knowledge that I probably wouldn't be chosen to be on The Tonight Show.

On learning how white people see him as a threat

That's one of the first lessons that I was taught in my life. Every Black parent has to have this conversation with their kid. And the way that you internalize that information might affect you. ... One of the first lessons I had to learn about myself was how much of a threat I was, and that's weird. Like to be a kid who constantly [was being told], "You're so cute! His Afro!" and pinch my cheeks and all these things.

And then one day you turn 11, and your dad [sits down and tells you], "You're not cute anymore." And that's all I kept with me, like, "Oh, I'm not cute anymore. I'm a threat." And my whole entire life that never left me, to the point where if I'm in a dark parking lot, I'll sit in the car for hours because I'm afraid of the threat that I posed to people – when women are walking in dark parking lots in the hotel that I'm staying in or that sort of thing. "I'll let you do the elevator. I'll go in this one by myself." And so that whole way of life, that affects you as an adult.

On changing his signature hairstyle, an Afro with a big pick

I kind of retired it. ... I just think I got tired of searching for it. Like the panic of "I gotta go back and get my Afro pick" was really just getting on my nerves.

And when I was quarantining I'd pretty much been wearing my hair braids, just so I wouldn't have to deal with the nightmare of doing my hair for an hour every day. Occasionally I bring my Afro out, but I'm kind of enjoying the anonymity of what life was like wearing a mask and having my hair braided, like the places I could go to and not be recognized. It's been kind of awesome. So I'm enjoying my newfound freedom without looking like Questlove.

On taking time to care for himself during the pandemic

Had this not happened, I would have probably been on an express lane to the next life. As you can see with all my peers in hip-hop, a lot of us ... thought that not getting shot in the club was the victory. "Ah, OK. I'm 35 now. I'm too old to get shot in the club," because that was always a concern in the '90s. Now there's a new getting "shot in the club," which is strokes, cardiac arrest, our mental health and whatnot. ... A lot of us can't even get past the age of 60; so many of my peers in hip-hop are succumbing ... in their 50s. Like 10 a year. So it's a fight to the finish. I'm at probably the best place I've [ever been] right now. I've lost over 100 pounds. I'm happier. I'm just happy to be alive.

Heidi Saman and Kayla Lattimore produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Andrew Flanagan adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2022 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.