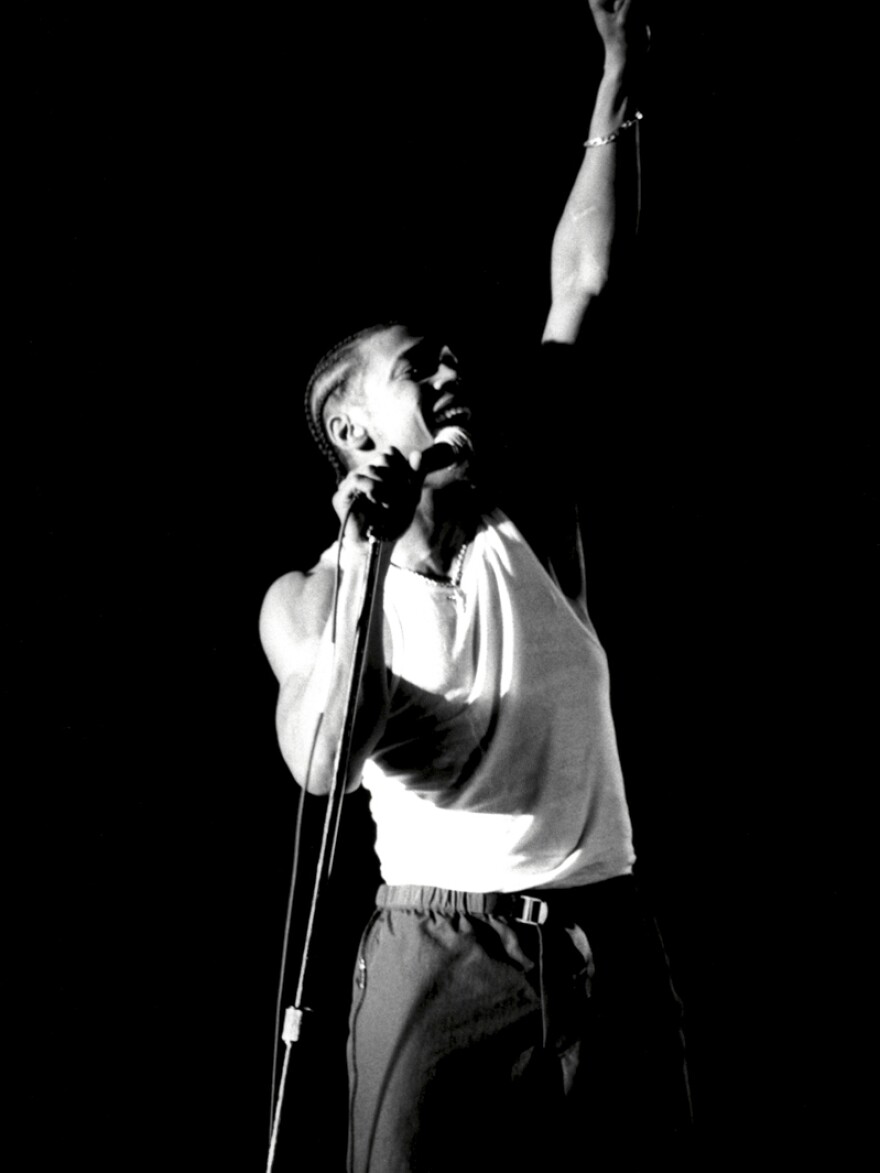

The conventional wisdom about Voodoo, in a few big ways, is wrong. Released on Jan. 25, 2000, the second album by D'Angelo was hailed as a high point of the neo-soul era. The music video for the single "Untitled (How Does It Feel)" — featuring the singer crooning shirtless with perfect white teeth, perfect muscles, perfect cornrows — announced him as the moment's new sex symbol. But as D'Angelo would later confess, he hated the way his breakout video sexualized his image. And as hindsight makes clear, Voodoo wasn't really a neo-soul album at all.

Black radio was changing quickly at the end of the 1990s, as artists like Jill Scott, Maxwell and Lauryn Hill melded R&B with slick hip-hop production and a coffee-shop poetry-night sheen. But D'Angelo had spent the past few years indoors, away from the vanguard. As part of The Soulquarians, a collective that also included superstar drummer Questlove, keyboardist James Poyser and heady, trippy producer J Dilla, he had logged countless hours holed up in Greenwich Village's Electric Lady studios, whose vintage equipment had previously helped artists like Stevie Wonder, The Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix make their masterpieces. As Nate Chinen of NPR's Jazz Night in America described in The New York Times, The Soulquarians were in their own world — jamming out to old Prince and Stevie bootlegs, transporting themselves and the music they made there to the past, not the future.

Russell Elevado was there, too. A rising producer and engineer, Elevado had been tapped a few years earlier to finish mixing D'Angelo's 1995 debut, Brown Sugar, after the original engineer left the project. As he got to know the artist, he introduced him to his favorite '60s and '70s rock records and grittier, more stylized production methods, and the two began enthusiastically plotting their next venture together.

"I grew up on classic rock and soul — like, Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, that's really where my roots are," Elevado says. "My whole concept was, hey, people are sampling these records. I can create those sounds — using the microphones they were using, using the consoles they were using, the same techniques — and make it our own thing organically."

Elevado recorded and mixed Voodoo with D'Angelo and his band over the course of three years, going to great lengths to ensure everything about the album and all its influences melded seamlessly. When it finally arrived in 2000, it came as a stealth throwback at a moment when R&B and soul felt caught up in something new. But while many today think of it as a masterpiece, it seems we still haven't figured out how to make sense of Voodoo: what box to place it in, how to pay it the respect it deserves, all the nuance and depth of a young black artist making a previous generation's black music.

Voodoo is so many things. It is jazz, soul and funk all at once. You can hear hip-hop's footprint in some of the songs, but it never dominates. While the influence of Prince and Funkadelic and Marvin Gaye is there on every track, it draws just as much inspiration from Hendrix and The Beatles. And for the artist, it was such an important statement that he waited nearly 15 years to follow it up. If it took time to see that Voodoo didn't live in the same music world as its peers in 2000, by now it has stopped feeling vintage — and started feeling timeless. I spoke with Russell Elevado about what it took to make Voodoo sound the way it does, and the legacy it maintains on its 20th birthday.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sam Sanders: You had been working in studios for over a decade when you were hired to engineer Voodoo, but it took a while for you to move into R&B and soul. Why do you think those artists eventually started to notice you?

Russell Elevado: When I first started engineering I was doing a lot of house music, with Frankie Knuckles and David Morales. I first started getting my feet wet with that, and doing hip-hop remixes with this producer Clark Kent. From there, more R&B people started recognizing what I was doing, and I started going through the R&B circuit.

Later on, I realized how much it was like the work I was doing on house music. Because the bass has to be right. And the kick drum should have its own presence to not get in the way of the bass. Striving to get that in my early part of my career, think I intuitively started to know how to make the bass pump without being too large, and get the impact of the drums. House music is all about the bass and drums, and I guess that filters into everything else I did.

When did D'Angelo come into your orbit, and how?

I had been working on an album for Angie Stone, who was managed by the same manager as D'Angelo, Kedar Massenburg; he also managed Erykah Badu at the time. They were looking for another engineer to finish Brown Sugar. He'd heard what I was doing, saw my mixes were sounding good. He played me the songs that were finished so far, and I was like, "Yeah, get me on this album. I'll do whatever — I love it." So he introduced me to D'Angelo.

How was that first meeting?

When we met, he introduced himself as Michael — and I thought this was just Angie's boyfriend. They were dating at the time, and he was coming in to visit Angie a lot.

Wait, you didn't know it was D'Angelo at first?

No! I was hanging out with "Michael Archer" for two weeks before I realized this was the same guy. He was like 18 years old, really laid back, a little on the shy side, kind of kept it low. Little did you know he was this amazing musical genius.

Once I started to mix those songs, I was like, "Hey, what if we made your voice distorted on this part? Or make the track sound rougher, so it's not as slick." He's like, "That sounds amazing, but seven songs are finished. We can't stray too far from the original vision of the album. But tell me more — I love your ideas." We really hit it off well. So we started listening to each other's records and the different things we were influenced by, and eventually started talking about the next album.

And Voodoo ends up sounding very different than Brown Sugar did. What's going on at the beginning of the album, on the first track? Are they at a séance or something?

That was actually a track that was recorded in Cuba. They went to take pictures for the album, and while they were there they were at a ceremony — like, Santería. So that's a remote recording of a real voodoo ritual.

In high school, I literally had three copies of this album: one at home, one in my car, and one in my locker at school. I was raised in this black Pentecostal church where I played the saxophone in the band, and we would sneak riffs from Voodoo into the church music because we were so obsessed with it.

A lot of people thought of it as a neo-soul classic. But if you listen, it's not at all what the other artists who were called neo-soul were doing at the time. They were really melding the hip-hop of the late '90s with R&B, and D'Angelo, save for maybe "Devil's Pie" or "Left and Right," was doing none of that.

Exactly. It was as if everyone else was still catching up to Brown Sugar and thinking that's a great blueprint to follow, and D'Angelo is just totally going to the next level.

Do you think it's fair to call Voodoo a neo-soul album?

No, I don't think so. Brown Sugar, I would call neo-soul. Voodoo, I think, stands on its own: It's really a soul and funk album, versus an R&B album. I consider it like how we would call a soul album back in the day, like Sly Stone, or even Sam Cooke. And I'm starting to recognize over the years that there's a lot of fusion on that album, too, where we were fusing a lot of rock elements.

Which songs? Give me an example.

"The Root" has sort of a Jimi Hendrix guitar lick, but it also reminds you of Curtis Mayfield — so, blending this psychedelic rock thing on top of funk-soul. "Playa Playa" is another good example: It's really funky, but there's a lot of these psychedelic elements. It was kind of like he was schooling me on a lot of funk music, and I was schooling him more on the rock side.

What kind of rock were you showing him?

Like, Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix and The Beatles. Because he grew up in a black community and was not exposed to a lot of quote-unquote "white music," which would have been rock or pop. He knew "Purple Haze," but he had no idea. Once he got it, it was like an epiphany: "Wow, I can't believe it — everybody was influenced by Jimi Hendrix." Prince was heavily influenced by Hendrix. Even Sly Stone, and especially Funkadelic and Parliament, they were all about Jimi, and if anything they were continuing what Jimi was doing after he died.

What song on Voodoo has the most spirit of Jimi in it?

I would have to say "The Root" — and in fact, that song grew out of a Hendrix jam at Electric Lady. It was Charlie Hunter and Questlove and D'Angelo, and they had just covered two or three Hendrix tunes: I think they played the actual song "Electric Ladyland," and maybe "Castles Made of Sand," something from Axis. "The Root" came from those jams, for sure.

"The Root" is structurally very complex. It's probably my favorite song on the album, but it took me the longest to get it — the chords are doing some hard, trippy stuff. How do you, as an engineer and a mixer, work with such a complex soundscape?

I guess it's in my DNA. As I was working, I would just think of what Jimmy Page would have done, or what Stevie would have done, what Eddie Kramer would have done, or George Martin — just incorporating those old-school sounds that I remembered. In the second verse there's this one line where every word is processed in a different way. It starts off distorted for two words, and the next word will be kind of echoey — all this different processing in one line.

You've said that part of your goal was make this music sound vintage, or like an original version of the old records that producers were sampling at the time. And listening now, I love that Voodoo sounds like it was recorded in 1975. How did you approach that task technically?

First of all, just fundamentally having a lot of sounds from that era in my brain. And then by adding a lot of distortion in creative ways. At the end of "Greatdayndamornin'," there's a little outro called "Booty." Those drums are processed through some distortion — I think I put it through a couple of guitar amps. I was doing a lot of that: experimenting with different types of microphones, processing through amplifiers, or overloading the line amps on the console to see if I could come up with an "oldish" sound.

Something like tape flanging, where the instrument has this whooshing sound — Queen used to do that a lot. I might not have known how they came up with it, but I would try to experiment and try to create it on my own. You can hear that towards the end of "Untitled": The song starts to build, and it's just riffing and riffing and he starts screaming. Towards the last minute I started flanging the entire mix, so it gets really wooshy and sounds almost like it's washing out.

When you're employing these techniques, how do you know when you've done enough? Because "Untitled" is also the song that stops very suddenly.

Well, that's another thing — the song cuts off like that because the tape runs out.

What do you mean, the tape runs out?

It was all recorded on tape, you know? So that's what happened — he wanted to keep going, but then the tape cuts off, so it ends like that. When we were finishing overdubs, he assumed that we would fade down it before it came to a complete halt. I was like, "You gotta leave it like that, man!" Because there's this Beatles song, "I Want You (She's So Heavy)," where it happened to them, too: It's this whole buildup that keeps going for two and a half minutes, and then it cuts off abruptly. So I played that for him, and he was like, "Yes. Let's do that." It was just before Pro Tools became a standard in the industry — everything was mixed and recorded to tape.

For folks who don't know music production, tell me a little about the difference between that process and digital recording.

Nowadays, everything is recorded digitally, but all of the past legends made their music on tape machines. Whereas digital is like a copy of the signal, tape is the purest form you're going to hear music in: The signal is recorded onto a part of the tape and it's physically there. In general, there's a warmer sound, more of a natural sound, and it gives you more of an impression of depth and width in the music. But also, with digital recording, you can undo something. With tape, if you want to go over a section, it's completely gone — you can't retrieve that information ever again. And it makes you better, because there's less room for errors.

I have a question for you, as a longtime D'Angelo fan: What is it about the way sings his words, where you never actually know what he's saying, but it doesn't matter? I've played this album thousands of times; I don't think I actually know half of the words.

[Laughing] Dude, I worked on the album and I don't know half the words. Yeah, it is a little bit of a running joke. We used to call it "D'Bonics."

Did you ever say, "All right, man — enunciate." Or did you not care?

You know, every once in a while. He'd ask me, too — he'd say, "Can you understand me?" And I'd be totally honest! He knew everybody was feeling the same way — management, the record label: "But what is he saying?" But you know, a lot of times he would sing something to get the right inflection and intonation, versus trying to articulate the word. It's more of a musical thing. And also, we were mixing his vocal level lower than normal. He liked it where the track kind of had him enveloped — not really on top of the mix, but more inside of the mix.

What do you think is the legacy of this album, 20 years on? What is the biggest lesson, the moral of the story, of Voodoo for us today?

It's an actual album, where you can put it on from start to finish and it's one piece of art, like it was back in the day — versus albums that have 15 filler tracks and three singles. And how a record can sound when there's an intimate setting, and you have these amazing musicians that are like-minded and are going for a certain feel. How much magic can be created by human beings playing their instruments, who have learned their craft over years and years of experience, coming into the studio and recording. A lot of that is lost in music today — just the organic process and the musicianship. It's refreshing to hear people making music like that.

Even to this day, I find myself hearing new things — just the layers in the engineering, the mixing, the production, the vocal work. It always sounds like it must have taken forever to make.

We were on and off in the studio for about three years. The first two years were incredible. The last year was a bit harder. We were running out of money — the label was not trying to get us back in the studio. And besides that, just keeping on the same vision: My mind was already moving on to other things that I could be doing. I'd learned so much from the making of the album that I wanted to try new things with other people. But the creation and the mixing and what we achieved is probably going to be the highlight of my career. I don't know if I'll be able to top that.

Sam Sanders is an NPR correspondent and host of the podcast It's Been a Minute with Sam Sanders.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.